This building project from the 1990s will make real estate more sustainable in the future

Nowadays, everyone is talking about sustainability, but even in the 1990s it was an important topic. And even then, unique sustainable projects emerged from which we can still learn today. A visit to Marleen Kaptein, one of the initiators of the sustainable community Lanxmeer in Culemborg, provided the proof.

Sustainability in the 1990s

In the early 1990s, the Dutch government had a plan to develop residential areas sustainably, in the form of what became known as “Vinex” districts. The ambition was there, but there was one big obstacle: according to the government, consumers were not yet willing to pay for sustainability. The budget for environmental measures was limited, and control soon fell into the hands of commercial developers. So little came of a sustainable implementation,” says Marleen Kaptein, visibly disappointed. “That was a real shame, because the time for sustainability was ripe and Vinex neighbourhoods offered the ideal conditions for creating a sustainable infrastructure.”

“In the 1990s, environmental slogans were things like “a better environment starts with yourself” and “take shorter showers”, which put the onus on the consumer. But that’s not something that gets people inspired. I wanted to build a bridge between government environmental policies and people in society by showing solutions in practice.“

– Marleen Kaptein, initiator ofEVA-Lanxmeer

Good examples have to come from practice

When government proved to be unable to reach people with its environmental policies, this got Marleen thinking. “I thought: let’s first see in practice what it means to live in an environmentally friendly neighbourhood. Because it improves the quality of our own lives.” Starting from this idea, Marleen wrote a project proposal for a national example for sustainable area development. “Initially, I shared my plans with a number of people in my network, such as architects, landscape architects and people from the energy sector. With them, I made a programme of requirements for the development of at least 200 sustainable homes, including infrastructure, an urban farm and a community centre.”

Momentum on sustainable housing estate EVA-Lanxmeer kicks in

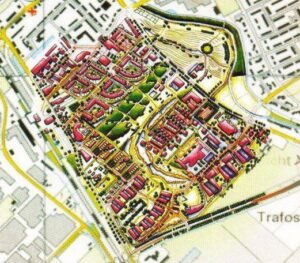

By the end of 1994, the plan was ready and a foundation for EVA (an abbreviation for the Dutch for “Ecological Centre for Education, Information and Advice”) had been established. Board members included professors from the Technical University Delft, Wageningen University & Research (WUR), a landscape architect from the Dutch Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment (VROM) and an energy expert. Then the project started gaining momentum. “Within a week, the municipality of Culemborg had heard of us and they were very interested in the project. We had a concept and they had a location: 28 hectares of agricultural land around a protected water catchment area just outside the city had just become available for a new use,” Marleen explains enthusiastically. “But there was one significant catch, though: no piling was allowed in the immediate vicinity of the protected area. That meant we had to build with a light foundation, so wood frame construction was the way to go. Of course, this was no problem for us, as it fitted in with our sustainability objectives. After all, wood is a lot more durable than concrete.”

“It was a perfect match. The municipality of Culemborg recognised their ambitions in the concept of the EVA Foundation and they offered to partner with us on the Lanxmeer project.“

– Marleen Kaptein

Essential conditions for the success of Lanxmeer

Important conditions for a successful Lanxmeer were a location and a good partner. The foundation found both in the municipality of Culemborg. “One essential condition is that a municipality takes the initiative to build such a residential community. With us, they offered to become a partner in the plan, and this is what a good partnership, on an equal footing, grew out of.” In addition, the involvement of various parties contributed to the success of the sustainable neighbourhood. Before the start we already had 80 responses from people who wanted to live in the neighbourhood. This helped enormously and some of them actively participated in the development of the neighbourhood. The BetuwsWonen housing association was also represented. The management of Waterbedrijf Gelderland was initially concerned about construction plans around their area, but after extensive explanation of our objectives they came around, and even became big proponents of the plan!”

Lanxmeer project lauded for inclusiveness and circularity

Today, Lanxmeer is a success that is praised both at home and abroad for its progressiveness. The houses are surrounded by a park that is maintained by the residents, and its features include a beautiful orchard and working stock farms. Houses are built of reusable materials and there are many opportunities for recreation close to home. Every detail has been thought through, and the infrastructure in the neighbourhood also fits in seamlessly with the sustainable philosophy. “Just look at our integrated water concept,” says Marleen. “Now the only thing going into the sewers is our toilet water. Clean rainwater is channelled from the roofs into several ponds along the water catchment area, and domestic wastewater is treated using helophyte filters. The dirty rainwater from the streets is fed into what we call ‘WADIs’ (Water Drainage Infiltration), which can both retain and infiltrate water. With this, we have almost closed the cycle.”

Three tips for the future

The message emanating from Lanxmeer is still relevant today. Whereas the focus today is mainly on gas-free, CO2 reduction and climate adaptation, we will also have to make a move towards circularity. Even in sustainable neighbourhoods, in housing construction we see very little to no use of reusable materials or materials that come “back into the chain” — this despite the fact that 40% of CO2 emissions come from concrete in construction. That is why Marleen concludes with three broad tips to make future sustainable projects a success as well:

- Get the right people in the right place

“I think this was a key success factor for us. Lanxmeer was realised with committed professionals from various disciplines, so that we really approached the project from various angles. A partner with sustainable ideals, like the municipality of Culemborg, is also essential for good cooperation.” - Think holistically, make connections

“There needs to be a more holistic perspective on spatial planning. Once you have that, it’s unthinkable to stick to just one theme, such as ‘energy-neutral houses’ or ‘circular construction’. We need to think holistically, make connections and use opportunities that locations offer. Only then will you get real change and optimal sustainability.” - Involve stakeholders and get their input

“Participation is extremely important for the success of a project. So make sure that you do not enter into a project with things too narrowly defined or too detailed. There must be room for co-creation. That is what really makes a project better!”

There are many opportunities to implement circular initiatives in buildings and construction projects – but also a lot of challenges. Read more about how to future-proof your building or contact us for tailor-made advice.